The Mission – Destroy

Brest!

The raid was a large scale affair for an action of its type.

It was months in the planning with the objective of wreaking havoc on a key

strategic anchorage for the French fleet at the port of Brest in western

Brittany. Naval bombardments of French ports had been undertaken before, one

such being that prosecuted against St Malo shortly before the Camaret

expedition. The difference with Brest was that the English planned to put

around 8,000 infantry ashore and gain a foothold in order to do some real

damage. Tollemache would lead the army attack which was to be transported by

Admiral Charles, Lord Berkeley. The fleet was substantial, comprising 38

English and 21 Dutch vessels including fire and hospital ships. Troops began

assembling in Plymouth from mid-May 1694.

|

| Former enemies sailed together to support the English landing. 69 English and Dutch ships were involved. |

Transportation was delayed through

adverse weather and it was only by early June that the armada was off Cape

Finisterre. The French fleet under de Tourville had recently sailed south from

Brest towards the Portuguese coast and bested a combined English and Dutch

fleet off Lagos.

Tollemache’s plan was to land at Camaret Bay, a small inlet

on the opposite shore to Brest and about seven miles south, overcome the

batteries and defences there then march on Brest in order to storm it. To do

this he had between twelve and fifteen battalions who would be ferried ashore

in large open well-boats built specifically for the job and travelling with the

fleet. All of this would be carried out under a bombardment from Berkeley’s

ships. Parallels with the Normandy Landings cannot have passed readers by!

Tollemache was a bold, perhaps rash commander and having

Cutts on the team will not have added a cool voice of reason. John Cutts had

already been wounded near fatally, three times whilst leading breach assaults

in Europe and Ireland. He would go on to be wounded several more times.

Berkeley too appears to have been a somewhat gung-ho leader and thus the reflective

counterweight to English fire-breathing resided with the Dutch. The senior

Dutch officers attached to the enterprise were mostly from the navy and would

not necessarily have been favourably perceived by English army officers who

believed they were not receiving adequate share of the war spoils since the 1688

coup d’état.

What they didn’t

know!

In an age of true political and military duplicity the bold

trio and their Dutch allies had been betrayed well in advance. King James now

resident in exile at St Germaine en laye had friends within the English

establishment. News of the plan to raid Brest had reached the French and King

Louis despatched none other than the great Vauban himself to strengthen the

defences of Brest and assume personal command of the forces in west Brittany.

Vauban was and perhaps still is considered history’s premier military engineer.

His genius remains in evidence all over France and modern Belgium and he is

quite possibly peerless in his achievements.

That the King would have assigned

he of all people to stymie the enemy’s attempts speaks volumes. This battle

turned out to be Vauban’s only field command during his entire career and he

discharged his duties flawlessly.

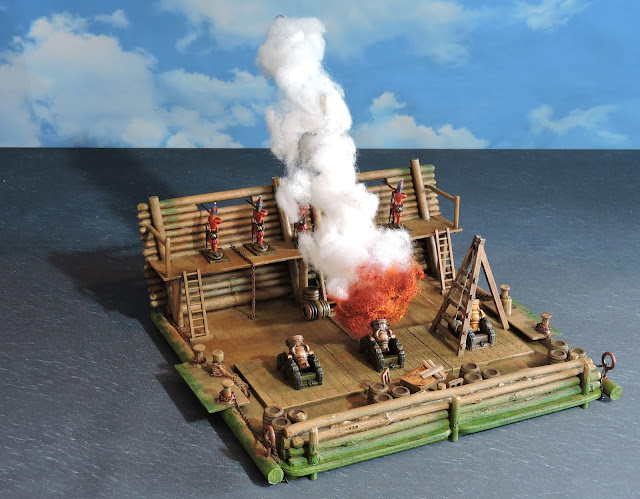

Vauban strengthened the already formidable castle at Brest,

the forts around Camaret and the larger bay in which Brest nestles. He built

numerous redoubts and emplacements, constructed trench works behind the beaches

and created what could fairly be described as a 17th century

Atlantic Wall with one distinct difference - this one worked. The area had over

300 cannon and 90 mortars with converging lines of fire, hidden batteries

invisible from the open sea and even from the mouth of the bay itself. It is

thought that eight large floating mortar platforms covered the fleet anchorage making

the concentration of firepower formidable.

I am sure many of you are ahead of me

and musing ‘that is a lot of prep and would have taken quite some time and

effort to complete’. Which begs the question; How far in advance did the French

know and who might have tipped them off?

|

| Even I wouldn't want to believe he dobbed in his own team. |

Smoking pistol?

Much to the discomfort of Churchill fans everywhere, the

most commonly accepted smoking flintlock appears to be in the right hand of

John, Earl of Marlborough. He had maintained a correspondence with King James

his estranged mentor pretty much throughout the turbulent period since

William’s arrival in England. A letter exists revealing the plan for the raid

written by Marlborough and sent to his old friend. Great men such as Winston

Churchill have set out to disprove the betrayal and recently such eminent minds

as the late Richard Holmes and David Chandler have contributed to the debate.

What is interesting is that Holmes and Chandler neither of them reticent about

expressing an opinion are somewhat equivocal on the subject of whether he did

or he didn’t. Why would he? Betraying his own side and being in some way

culpable for the death of upwards of 1,500 English soldiers and sailors seems

unthinkable even for a political operator of Churchill’s calibre. If he did, the

reasons may be very human indeed. The first is self-preservation in that he was

hedging his bets with James and the French. The Allies had recently experienced

bloody defeat at Steenkirke and Neerwinden and the outcome of the whole 1688

adventure may have been in doubt.

Anti-Jacobite purges in the English army

continued well into 1696 so fragility of the Williamite position may have

driven Churchill the survivor to keep all personal options on the table.

He may simply have been jealous of the advancement in

Tollemache’s fortunes perceiving them to be at the expense of his own. Marlborough

was known to be egotistical, greedy and vain. At a time when truly massive

fortunes were being made through military adventurism he may have been smitten

by the green eyed monster.

|

| The Battle of La Hogue on May 23rd 1692 had destroyed an invasion fleet destined to return King James to England |

Maybe he didn’t do it. Great pains have been taken to prove

that the letter was written too late to have been the source of the betrayal and

that someone else told the French way before Churchill’s missive arrived at the

Jacobite Court in exile. If this is true, why did he write the letter in the

first place? Perhaps as an insurance policy or as an act of conscience. The

matter has been obscured by a variety of counter argument and convoluted

rationale against yet, the possibility remains that Marlborough was the source

of the leak.